Tenang's Ville

Search This Blog

Monday 9 May 2011

Stage

THEATRE SPACES

Theatre: a space where a performance takes place, a large machine in the form of a building specialized for presenting performances.Stage types:

Proscenium stage:A proscenium theatre is what we usually think of as a "theatre".

It's primary feature, is the Proscenium, a "picture frame" placed around the front of the playing area of an end stage.

Theframe is the Proscenium; the wings are spaces on either side, extending off-stage. Scenery surrounds the acting area on all sides except side towards audience, who watch the play through frame opening. "Backstage" is any space around the acting area out of sight of the audience.

Thrust theatre:

A Stage surrounded by audience on three sides. The Fourth side serves as the background.

In a typical modern arrangement: the stage is often a square or rectangular playing area, usually raised, surrounded by raked seating.

End Stage:

A Thrust stage extended wall to wall, like a thrust stage with audience on just one side, the front.

"Backstage" is behind the background wall. There is no real wingspace to the sides, although there may be entrances there. An example of a modern end is a music hall, where the background walls surround the playing space on three sides. Like a thrust stage, scenery primarily background.

Arena Theatre:

A central stage surrounded by audience on all sides. The stage area is often raised to improve sightlines.

Flexible theatre:

Sometimes called a "Black Box" theatre, these are often big empty boxes painted black inside. Stage and seating not fixed. Instead, each can be altered to suit the needs of the play or the whim of the director.

Profile Theatres:

Often used in "found space" theatres, i.e. converted from other spaces.

The Audience is often placed on risers to either side of the playing space, with little or no audience on either end of the "stage". Actors are staged in profile to the audience. It is often the most workable option for long, narrow spaces.

Scenically, is most like the arena stage; some background staging possible at ends, which are essentially sides. A non-theatrical form of the profile stage is the basketball arena, if no-one is seated behind the hoops.

Sports Arenas:

Sports arenas often serve as venues for Music Concerts. In form they resemble very large arena stage (more accurately the arena stage resembles a sports arena), but with a retangular floorplan. When used for concert, a temporary stage area is set up as an end stage at one end of the floor, and the rest of the floor and the stands become the audience. Arenas have their own terminology; see below.

Parts of a Proscenium Theatre:

The Proscenium is the defining element of proscenium theatre, basically a big picture frame dividing acting space from audience. All directions defined according to this division of the space by proscenium.Stage directions are given from the viewpoint of an actor center stage facing the audience, Stage Left is the actors left, Stage Right to the actor's right. Downstage is towards the audience, Upstage is towards the back wall of the stage. The Plaster Line (PL) is a line running from the back of one side of the proscenium arch to the other proscenium. The Center Line (CL) runs upstage/downstage half way between prosceniums and perpendicular to the Plaster Line.

Everything downstage of the Plaster line is called Front of House, or FOH. Occasionally it is also called "Ante-proscenium" which means "before the proscenium". Anything the audience can see on the stage is on-stage. Anything on the stage but out of the audience view is off-stage or backstage. Wings are the sides of the stage, and the Fly Loft or Scene House is the space above the stage. The floor is called the Deck.

The part of the stage in from of the Proscenium is the Apron, or sometimes the Thrust. The Audience seating is the Auditorium or the House.

Stage directions: L,C,R,US, DS etc., Plaster and Center Lines:

Proscenium, FOH, Wings, Apron, Traps and traproom:

Proscenium, FOH, Wings, Apron, Traps and traproom: Scene house, Fly loft, Lock rail, Fly rail, Loading rail, Grid

Scene house, Fly loft, Lock rail, Fly rail, Loading rail, GridHouse, Box boom, Beams, Cove, Booth

Ancillary areas:

Ancillary areas:*scene and prop shops,

*storage,

*light storage and maintenance,

*costume shop and storage,

*dressing rooms, green room,

*lobby & box office, publicity, administration.

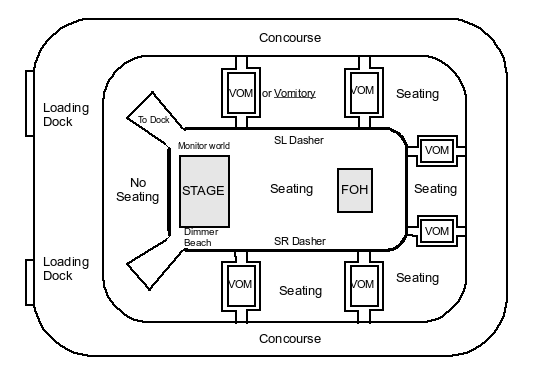

Parts of an Arena:

An Arena is designed for sporting events first. Setting up a concert means fitting it into a space meant for a different kind of event. Compromise and accomodation is frequently required.The stage is usually set up as an End Stage, or occasionally in the center as an "Arena" Stage.

Directions in Thrust, Arena, and Profile Stages:

Directions more problematic, audience isn't in any one direction.Thrust theatres:

Assign middle section of three-sided audience as "downstage".

Care must be taken to remember sides are also "downstage" for audience there.

Arena stages:

All directions are "downstage".

Common schemes used:

*Compass directions (north, south,east, west)

*"Clock" (12:00, 3:00, 6:00, 9:00) with direction of 12:00 assigned.

*Assign names to parts of space (Ar.A, Ar.B, Ar.C, etc.); may be different in subsequent productions

(http://www.ia470.com/primer/theatres.htm)

Tuesday 8 March 2011

4 Principles in Scenography and Elements of Scenography

Space/Place

(This is my opinion in place of elements of Sceno into the 4 principles of Scenography)

Presentational acting and representational acting

Representational acting

Presentational vs. Representational

Presentational acting and representational acting

Presentational acting and the related representational acting are critical terms use within theatre aesthetics and criticism.

Due to the same terms being applied to certain approaches to acting that contradict the broader theatrical definitions, however, the terms have come to acquire often overtly contradictory senses.

In the most common sense (that which relates the specific dynamics of theatre to the broader aesthetic category of ‘representational art’ or ‘mimesis’ in drama and literature), the terms describe two contrasting functional relationships between the actor and the audience that a performance can create.

In the other (more specialized) sense, the terms describe two contrasting methodological relationships between the actor and his or her character in performance.

The collision of these two senses can get quite confusing. The type of theatre that uses ‘presentational acting’ in the first sense (of the actor-audience relationship) is often associated with a performer using ‘representational acting’ in the second sense (of their methodology). Conversely, the type of theatre that uses ‘representational acting’ in the first sense is often associated with a performer using ‘presentational acting’ in the second sense. While usual, these chiastic correspondences do not match up in all cases of theatrical performance.

Presentational acting

‘Presentational acting’, in this sense, refers to a relationship that acknowledges the audience, whether directly by addressing them or indirectly through a general attitude or specific use of language, looks, gestures or other signs that indicate that the character or actor is aware of the audience's presence. (Shakespeare's use of punning and wordplay, for example, often has this function of indirect contact.)

Representational acting

‘Representational acting’, in this sense, refers to a relationship in which the audience is studiously ignored and treated as 'peeping tom' voyeurs by an actor who remains in-character and absorbed in the dramatic action. The actor behaves as if a fourth wall was present, which maintains an absolute autonomy of the dramatic fiction from the reality of the theatre.

Robert Weimann argues that:

Each of these theatrical practices draws upon a different register of imaginary appeal and "puissance" and each serves a different purpose of playing. While the former derives its primary strength from the immediacy of the physical act of histrionic delivery, the latter is vitally connected with the imaginary product and effect of rendering absent meanings, ideas, and images of artificial persons' thoughts and actions. But the distinction is more than epistemological and not simply a matter of poetics; rather it relates to the issue of function.

| Conventionalized presentational devices include the apologetic prologue and epilogue, theinduction (much used by Ben Jonson and by Shakespeare in The Taming of the Shrew), the play-within-the-play, the aside directed to the audience, and other modes of direct address. These premeditated and ‘composed’ forms of actor-audience persuasion are in effect metadramatic andmetatheatrical functions, since they bring attention to bear on the fictional status of the characters, on the very theatrical transaction (in soliciting the audience’s indulgence, for instance), and so on. They appear to be cases of ‘breaking frame’, since the actor is required to step out of his role and acknowledge the presence of the public, but in practice they are licensed means of confirming the frame by pointing out the pure facticity of the representation. |

| Keir Elam, The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama, p. 90 |

Presentational vs. Representational

Both Stanislavski and Hagen, in their text books for actors, adhere to a mode of theatrical performance that starts with the subjective experience of the actor, who takes action under the circumstances of the character, and trusts that a form will follow. They deem it more useful for the actor to focus exclusively on the fictional, subjective reality of the character (via the actor's "emotional memory" or "transferences" from his own life), without concerning himself with the external realities of the theatre. Both teachers were fully aware of the 'outside' to the dramatic fiction, but they believed that, from the actor's perspective, these considerations do not help the performance, and only lead to false, mechanical acting.

Many types of drama in the history of theatre do make use of the presentational 'outside' and its many possible interactions with the representational 'inside'—Shakespeare, Restoration comedy, and Brecht, to name a few significant examples. However, both Stanislavski and Hagen applied their processes of acting towards these types of drama as well, fully aware of their unique requirements to the audience. Hagen stated that style is a label given to the "final product" by critics, scholars, and audience members, and that the "creator" (actor) need only explore the subjective content of the playwright's world. She saw definitions of "style" as something tagged by others onto the result, having nothing to do with the actor's process.

Shakespearean drama assumed a natural, direct and often-renewed contact with the audience on the part of the performer. 'Fourth wall' performances foreclose the complex layerings of theatrical and dramatic realities that result from this contact and that are built into Shakespeare's dramaturgy. A good example is the line spoken by Cleopatra in act five of Antony and Cleopatra (1607), when she contemplates her humiliation in Rome at the hands of Octavius Caesar; she imagines mocking theatrical renditions of her own story: "And I shall see some squeaking Cleopatra boy my greatness in the posture of a whore" That this was to be spoken by a boy in a dress in a theatre is an integral part of its dramatic meaning. Opponents of the Stanislavski/Hagen approach have argued that this complexity is unavailable to a purely 'naturalistic' treatment that recognizes no distinction between actor and character nor acknowledges the presence of the actual audience. They may also argue that it is not only a matter of the interpretation of individual moments; the presentational dimension is a structural part of the meaning of the drama as a whole. This structural dimension is most visible in Restoration comedy through its persistent use of the aside, though there are many other meta-theatrical aspects in operation in these plays.

In Brecht, the interaction between the two dimensions—representational and presentational—forms a major part of his 'epic' dramaturgy and receives sophisticated theoretical elaboration through his conception of the relation between mimesis and Gestus. How to play Brecht, in regard to presentational vs. representational has been a controversial subject of much critical and practical discussion. Hagen's opinion (backed up by conversations with Brecht himself and the actress who was directed by him in the original production of "Mother Courage") was that, for the actor, Brecht always intended it to be about the character's subjective reality—including the direct audience addresses. The very structure of the play was enough to accomplish his desired "alienation."

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presentational_acting_and_Representational_acting)

contributions of Appia, Craig, Wilson and etc in creating special environment / visuals on stage.

Adolphe Appia

| Name: | Adolphe Appia |

| Birth Date: | 1862 |

| Death Date: | February 29, 1928 |

| Nationality: | Swiss |

| Gender: | Male |

| Occupations: | Stage and Lighting Designer |

-Appia had no lovefor the use of the proscenium stage, elaborate costumes, or painted sets. Instead, he favored powerful, suggestive stagings that would create an artistic unity, a blending of actor, stage, lighting, and music. After a long study of the operas, Appia concluded that there was disunity because of certain jarring visual elements. The moving actor, the perpendicular settings, and thehorizontal floor were in conflict with one another. He theorized that the scenery should be replaced with steps, ramps, platforms, and drapes that blended with the actor's movements and thehorizontal floor. In this way the human presence and its beauty would be accented and enhanced. For Appia, space was a dynamic area that attracted both actor and spectator and brought about their interaction. Complementing his concept of space was his belief that lighting should be used to bring together the visual elements of the drama.

-Appia evolved his own theory that the rhythm inherent in a text is the key to every gesture and movement an actor uses during a performance. He concluded that the mastery of rhythm could unify the spatial and other elements of an opera into a harmonious synthesis.

-Appia's genius was finally recognized and his theories prevailed in spite of the critics. His theories of staging, use of space, and lighting have had a lasting influence on modern stagecraft.

-"For him, the art of stage production in its pure sense was nothing other than the embodiment of a text or a musical composition, made sensible by the living action of the human body and its reaction to spaces and masses set against it."

Edward Gordon Craig

| Name: | Edward Gordon Craig |

| Birth Date: | 1872 |

| Death Date: | 1966 |

| Nationality: | English |

| Gender: | Male |

| Occupations: | designer, actor, director |

-Aside from his difficulties with personality conflicts (Craig was known as an eccentric), his ideas were far ahead of his time. He believed in the director as the ultimate creator, one who must initiate all ideas and bring unity to a production. He created the idea of the actor as "ubermarionette," whose movement was not psychologically motivated or naturalistic, but rather symbolic. The actor should be like a mask for the audience to interpret. Finally, he introduced a new stagecraft--one based on the magic of imagination rather than on everyday details.

-If Craig's actual work was limited, and sometimes impractical because of technical limitations, his writing was prolific. In 1898 he launched the theater journal The Page; in 1908 The Mask (until 1929); and from 1918 to 1919 he wrote The Marionette. He also published The Art of the Theatre (1905), On the Art of the Stage, Towards a New Theatre, Scene, The Theatre Advancing, and Books and Theatres, as well as biographies of Henry Irving and his mother.

-Craig's work in the theater and his writings have influenced many of the 20th century's innovators, including Stanislavsky, Meyerhold, and Brecht. He continued to be a source of inspiration for many years--many of the ideas that he developed in the early part of the 20th century were not realized on the stage until the 1980s. Edward Gordon Craig died at the age of 94 in 1966.

Svoboda, Josef

-(1920–2002) Designer and architect, Czech Republic. Svoboda has worked on many world stages, such as Chekhov’s Tri sestry(Three Sisters, 1967), at the Old Vic, London, directed by Laurence Olivier, and Goethe’s Faust II (1991), at the Piccolo Teatro di Milano, directed by Giorgio Strehler. By means of kinetic and light designs, he activates the stage space, which he understands as a dramatic component contributing to the action.

-He also makes use of stage vehicles (Kundera’sMajitelé klícu (The Owner of the Keys), National Theatre Prague, 1962), and suspended architectural elements (Romeo and Juliet,National Theatre Prague, 1963). With light he creates dematerialised objects (Wagner’sTristan and Isolde, Grand Opéra Geneve, 1978) and imaginary spaces. He uses mirrors to reflect and outline the stage action as well as the public many times over (Pirandello’s I giganti della montagna (The Mountain Giants), Theatre Beyond the Gate II (Za Branou II), Prague, 1994), and various projection techniques on multiple and moving spaces, television cameras allowing instant reproduction of shots on the stage itself (Nono’s Intoleranza, The Opera Group, Boston, 1965), or holography and laser beams (Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), Munich, 1970). He is a true wizard of the stage, casting his spell by means of modern science and technology.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)